Why beheading?

| Share: |

Last week, meanwhile, Australian police arrested 15 suspects allegedly linked to Islamic State; they are accused of plotting to publicly behead a victim abducted at random.

Why this obsession with cutting off people's heads?

Clearly the terrorists relish the horror beheading evokes in America and other Western democracies, as well as the fear it inspires among Kurds, Shiites, or other local forces standing in the path of their juggernaut. Psychological warfare is an essential element in Islamic State's military strategy, writes Shashank Joshi, a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in London. Even when heavily outnumbered, Islamic State has been able to leverage its reputation for implacable brutality "to dissuade Iraqi forces from ever seeking battle." And by killing American and British hostages with such sadistic relish, it aims to intensify the desire of many in the West to wash their hands of involvement in Iraq once and for all.

But there are other ways to terrorize, other gruesome means of mass murder — suicide bombings, poison gas, hijackings. Why the emphasis on beheading?

No doubt part of the explanation is that beheadings tend to draw more attention than suicide bombings and exploding cars. Deadly though they are, car bombs and shootings have lost much of their shock value in Western eyes. It takes an unusually high death toll for a bombing in Iraq to attract as much media attention as the decapitation of a single hostage by an English-speaking Islamist wielding a knife. Terrorists crave attention, more now in the digital age, perhaps, than ever before. Islamic State and other jihadist groups have many ways to commit mass murder. But for generating a spectacle that will be noticed — and shuddered at — the world over, sawing off the head of an American journalist or a European relief worker, then uploading the video to the Internet, is hard to beat.

Yet beheadings, too, can lose their shock value. It wasn't all that long ago that decapitation was a familiar punishment in Western culture. As late as 1977, the guillotine was still being used for executions in France. In the colonial era, severed heads of criminals were sometimes displayed on Boston Common. Plus, modern video games and ultrarealistic computer graphics make it easier than ever to grow inured to almost any image or scene, no matter how grisly or intense or intimate.

But the beheadings aren't just a fashion.

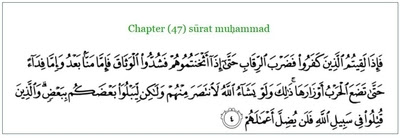

There is more to the Islamist passion for decapitation than psychological warfare and a hunger for notoriety. There is also Muslim theology and history, and a mandate going back to the Koran. In a 2005 study published in Middle East Quarterly, historian Timothy Furnish quotes the famous passage at Sura 47:4: "When you meet the unbelievers, smite their necks." For centuries, Furnish observes, "leading Islamic scholars have interpreted this verse literally," and examples abound throughout Islamic history.

Yet Western leaders keep insisting that the beheading of "infidels" is unrelated to the jihadists' religious outlook.

"When you meet the unbelievers,

smite their necks," the Koran commands. For centuries leading Islamic

scholars have interpreted this verse literally. Examples of mass

beheadings abound throughout Islamic history.

|

President Obama repeatedly makes the same assertion. When he outlined new military steps against Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) in a televised address this month, he avowed categorically: "ISIL is not Islamic."

Alas, ISIL disagrees. And so do the radicalized Western Muslims flocking to the Middle East to join its brutal jihad, many of them stimulated by propaganda videos that feature the beheading of "unbelievers." To millions of moderate and peaceable Muslims the world over, beheadings in the name of Islam may seem a terrible defilement of the religion they love. To a fanatical Islamist minority, they are just what Allah demands.

It may take a long while to destroy that enemy, but surely the first step is to call it what it is.

(Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe).